I have recently had a technical article about Location-Based Publishing and Services published at Dev.Opera. It’s all about the rising use of geographical coordinates in association with media on the Web, and how to get involved.

For the benefit of the Dharmafly archives, I’ve copied the article below.

Introduction

Geocoded content is transforming our Web. By adding geographical coordinates (latitude and longitude) to our media, we can help others find it through location-based search engines and web maps.

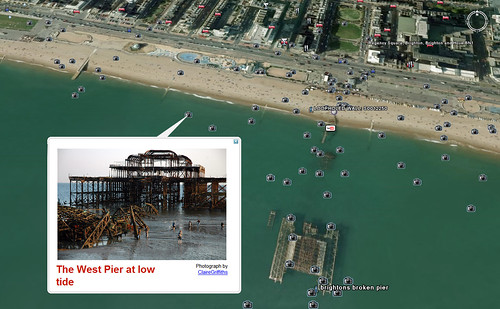

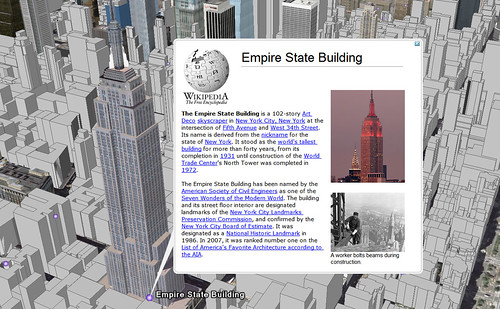

The tools for publishing geocoded media are more accessible and widespread than they’ve ever been, and we are finding all sorts of ways to put our content on the Map. Figure 1 shows a typical example.

Figure 1: A web map (Google Earth), displaying user-generated content.

There’s no limit to the variety of geo content. It could be anything: a listing of houses for sale in a neighbourhood, photos taken while travelling or a stream of local news stories.

A wave of geo innovation is under way and it has the potential to connect local populations and to communicate news and ideas from every corner of the planet. If the World Wide Web has lured people away from their own neighbourhoods, then geo is the technology that will bring it back.

In this article, we’ll look at ways that you can geocode your content, using data formats such as the location nanoformat, GPX and combinations of geocoded microformats in HTML.

Where Am I?

Ever since the first cave paintings of stellar constellations, and the first attempt to condense the geographical knowledge of an entire empire on to a had a thirst to plot the location of just about everything that we know exists.

Figure 2: Ptolemy’s world map.

We’ve used the Map to find ourselves and to see where we’re going. It is both a mirror and a lens, giving feedback on the world and helping us plan our next move. It has been a catalyst for our pursuits, as we’ve hunted trade routes and treasures, and followed pathways into mind-expanding new vistas and cultures…

A Place For Everything

On the Web, we tend to navigate by subject, using keywords and tags (e.g. “world music”). The rise of blogging gave us new possibilities for navigating via time (e.g. “most recent” posts and comments), and social networking now lets us explore the context of social relationship (e.g. posts and recommendations by “contacts”, “friends” and “followers”). But into the melting pot comes another axis of meaning: location.

“Where is it?”, “where will it be?”, “where are you now?”, “what is nearby?” Given the option, you’ll find that searching for content by location can be every bit as useful as the subject, timing or person who published it.

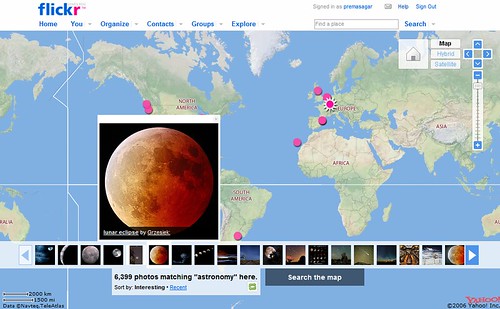

Let’s say you get fired up by astronomy… You could explore other astronomers’ photos on a world map, showing the places where the photos were taken, as seen in Figure 3:

Figure 3: The astronomy world map on Flickr.

You could even stay up to date with new photos by subscribing to the geocoded feed, to be read in a feed reader or plotted inside a mapping application (e.g. Google Earth, Yahoo Maps, GPS unit – either a standalone handset like the one in Figure 4, or a GPS phone, camera or other integrated device.

Figure 4: A GPS handset.

You can use these devices to record a log of your movements over time and to note any places of interest (‘waypoints‘). These locations can be transmitted live to another device via Bluetooth, streamed directly into the Web or transferred to a personal computer.

An increasing number of grassroots projects, such as Open Street Map and Free The Postcode, harness the global community of GPS users and challenge the traditionally top-down approach of compiling map data.

Instead of GPS, you might use a mobile application or service such as Zone Tag to determine your position from the mobile phone masts nearby. Or you might use a web map to find a place, search by postal address, or use a number of other methods.

Most often, you will need these coordinates in decimal form. This can be converted from the traditional degrees, minutes and seconds representation of coordinates.

Let us now look at some of the developing geo web standards, which allow us to weave location into our content. Imagine that you’re at The West Pier of Brighton, UK:

Figure 5: The West Pier of Brighton.

The latitude is 50.818967 and the longitude is -0.151934 (map).

HTML Meta Tags: The Old School Way

In the days before the World Wide Web, Usenet users could broadcast their location by including their “ICBM address” in the signature of their messages. This allowed the network of users to be geographically mapped.

This practice was carried over to the Web, where a web page could be geocoded by adding “ICBM” and/or “geo.position” meta tags to the document head (a geo tag generator helps to simplify the process):

<head>

<meta name="DC.title" content="The West Pier" />

<meta name="ICBM" content="50.818967, -0.151934" />

<meta name="geo.position" content="50.818967;-0.151934" />

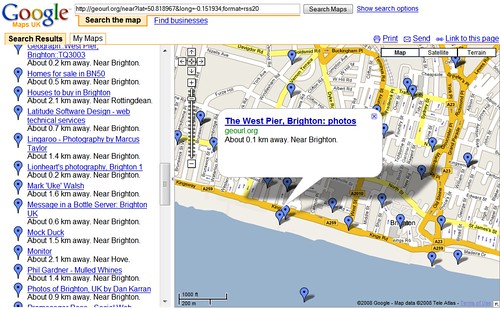

</head>Services such as GeoUrl can be used to find such a geocoded site. For example, websites near the West Pier (or see the feed visualised in Google Maps):

Figure 6: The GeoURL service allows you to find the location of URLs.

Photos and their EXIF Data

As a geo-photographer, you can use a tool such as GPicSync, RoboGeo or GPSTagr to synchronise your photos with your GPS handset’s log. Alternatively, you might use a GPS camera, or a specialist GPS unit (see Figure 7) that can directly geocode the image files on your camera’s memory card:

Figure 7: A GPS unit for geocoding image files on a memory card.

This geo information is added to the photos’ EXIF data, which stores such details as the time each photo was taken, shutter speed, etc. Alternatively, you could upload photos to a photo-sharing website and drag each photo on to a map (e.g. on Flickr, Panoramio or Locr).

GPX

GPS devices store data in a number of different formats. However, when they communicate with other devices and applications, they often use an XML language called GPX:

<gpx>

<wpt lat="50.818967" lon="-0.151934">

<name>The West Pier</name>

<time>2008-03-20T13:57Z</time>

</wpt>

</gpx>In this simplified example, the <wpt> element describes a ‘waypoint’ – a manually logged point of interest. The language can describe a number of other useful features and can be interchanged with other formats using tools like GPSVisualizer and GPSBabel.

Geotagging

Whenever a post can be “tagged” (such as on a blog, or a media-sharing website), it can also be “geotagged” with the location coordinates:

geo:lat50.818967

geo:lon-0.151934

geotaggedThe first tag gives the latitude, the second the longitude and we’ve added a third tag, “geotagged”, so that the post can be easily found in a search for geotagged media (see Figure 8):

Figure 8: A search for blog posts with a “geotagged” tag on Technorati.

Some video-sharing sites, such as Viddler and Motionbox, allow tagging of the video timeline. This enables individual segments of video to be geotagged.

Microblogging with the Location Nanoformat

Surely the simplest of all publications is the humble txt msg ;)

You can geocode your status updates (on, say, Twitter or Jaiku) by simply adding L: (upper-case) or l: (lower-case), along with your coordinates to the end of the message:

This place is beautiful. l:50.818967, -0.151934‘Nanoformats‘ are a growing collection of highly simplified, standardised ways to add semantic meaning to short bursts of content, such as text messages. Some early applications that use the location nanoformat are Twittervision (Figure 9) and Twitterwhere, which let you track Twitter users and their messages on a world map:

Figure 9: Twittervision.

The BBC World Service’s Bangladesh River Journey (see Figure 10) used geocoded Twitter messages to synchronise the location of a stream of different media publications:

Figure 10: The BBC Bangladesh River Journey mashup.

Some applications also recognise place names:

This place is beautiful. l:The West Pier, Brighton, UKThey achieve this by looking up the place name and retrieving coordinates from a database such as the Geonames web service, another community mapping project.

geo Microformat for HTML

We can mark up locations in HTML with the geo microformat:

This place is beautiful.

<span class="geo">

<span class="latitude">50.818967</span>

<span class="longitude">-0.151934</span>

</span>Note that, in this example, we could have used any HTML element instead of <span>, if that would have made better sense in context. In most cases, microformats do not require specific element types – rather, it is the class attributes of the elements that matter.

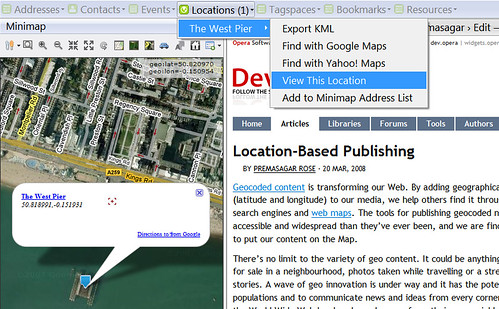

Just like any other HTML content, you can then go on to use a CSS stylesheet to highlight or embellish these geo elements, or perhaps hide them from view, and JavaScript on the page could be used to interact with the geo elements. In addition, browser extensions such as Operator or Minimap offer a number of actions for each location:

Figure 11: The Minimap Firefox extension.

The geo data on the page could also be parsed and converted by an external parser and visualised on another website.

geo Microformat Shortcut

A simple way to add machine-readable coordinates to HTML, without cluttering up the page for human readers, is to use a proposed shortcut for the geo microformat that utilises the <abbr> element design pattern:

<abbr class="geo" title="50.818967;-0.151934">

The West Pier, Brighton, UK

</abbr>A software program could read this snippet and determine that the text “The West Pier, Brighton, UK” more specifically refers to the location at latitude 50.818967, longitude -0.151934.

geo + adr Microformat

One of the most useful properties of microformats is that they can be grouped and nested within each other, to form compound microformats.

We could, for example, have placed the geo microformat inside an adr (address) microformat, to indicate that these are coordinates for a particular postal address or place name:

This place is beautiful.

<span class="adr">

<span class="extended-address">The West Pier</span>,

<span class="locality">Brighton</span>,

<abbr class="country-name" title="United Kingdom">UK</abbr>

(<span class="geo">

<span class="latitude">50.818967</span>,

<span class="longitude">-0.151934</span>

</span>)

</span>This produces the following output:

This place is beautiful. The West Pier, Brighton, UK (50.818967, -0.151934)The commas and brackets in this example are for human readability (most important!) and have no effect on the machine-readable microformat.

Using the <abbr> design pattern, our geo + adr microformat might instead look like this:

This place is beautiful.

<abbr class="geo" title="50.818967;-0.151934">

<span class="adr">

<span class="extended-address">The West Pier</span>,

<span class="locality">Brighton</span>,

<abbr class="country-name" title="United Kingdom">UK</abbr>

</span>

</abbr>geo + hCard

Geo can also be used (with or without the postal address) within an hCard microformat, to mark up contact details for a person or organisation:

<div class="vcard">

<span class="fn">John Smith</span>

<span class="adr">

<span class="extended-address">The West Pier</span>,

<span class="locality">Brighton</span>,

<abbr class="country-name" title="United Kingdom">UK</abbr>

(<span class="geo">

<span class="latitude">50.818967</span>,

<span class="longitude">-0.151934</span>

</span>)

</span>

</div>geo + hAtom Microformat

Another proposed, but as yet not finalised, use of the geo microformat is within the hAtom microformat.

hAtom is a way to build HTML with the same semantic structure as an Atom or RSS feed. An hAtom entry includes descriptive information about the post, such as its title, author and time of publication. This transforms a website into something akin to a massive Atom or RSS feed. New content can be picked up by feed readers directly from the HTML and, assuming the website keeps a logical URL structure, its entire archive of posts becomes automatically available as a web service API, with no back-end scripting required.

When you add geo to hAtom, it is analogous to moulding standard RSS into GeoRSS – that is, a geo-coded RSS or Atom feed:

<div class="hentry">

<h3 class="entry-title">The West Pier</h3>

<p class="entry-content">This place is beautiful.</p>

<address class="vcard author">

<span class="fn">Premasagar</span>

</address>

<a rel="bookmark" href="http://twitter.com/statuses/33333/">

<abbr class="updated" title="2008-03-20T13:57Z">3 hours ago</abbr>

</a>

(<span class="geo">

<span class="latitude">50.818967</span>,

<span class="longitude">-0.151934</span>

</span>)

</div>GeoRSS is used as the standard mechanism for exchanging geocoded publications on the Web (and KML is fast becoming the most common way to visualise it). By marking up your websites in geo + hAtom, you align your content with that transport mechanism, giving it the potential for more widespread distribution.

hCalendar + geo Microformat

Geo can be used within the hCalendar microformat to provide the location of an event – both historical and upcoming events. Even fleeting, passing thoughts (or ‘tweets’) can be represented, like so:

<div class="vevent">

<h3 class="summary">The West Pier</h3>

<p class="description">This place is beautiful.</p>

<a class="url" href="http://twitter.com/statuses/33333/">

<abbr class="dtstart" title="2008-03-20T13:57Z">3 hours ago</abbr>

</a>

<p class="location">

<span class="adr">

<span class="extended-address">The West Pier</span>,

<span class="locality">Brighton</span>,

<abbr class="country-name" title="United Kingdom">UK</abbr>

(<span class="geo">

<span class="latitude">50.818967</span>,

<span class="longitude">-0.151934</span>

</span>)

</span>

</p>

</div>The dtstart class in hCalendar is for the date-time of the start of the event. This is written according to the ‘datetime design pattern‘, which is common to all microformats that describe time.

hCalendar + geo + hAtom Microformat

For some uses, geocoded hAtom and hCalendar microformats can be combined within the same block of HTML. For example, an event (hCalendar) might be posted as a feed entry (hAtom). Or a feed entry (hAtom) might describe a passing moment (hCalendar):

<div class="vevent hentry">

<h2 class="summary entry-title">The West Pier</h2>

<p class="description entry-content">This place is beautiful.</p>

<address class="vcard author">

<span class="fn">Premasagar</span>

</address>

<a class="url" rel="bookmark" href="http://twitter.com/statuses/33333/">

<abbr class="dtstart updated" title="2008-03-20T13:57Z">3 hours ago</abbr>

</a>

<p class="location">

<span class="adr">

<span class="extended-address">The West Pier</span>,

<span class="locality">Brighton</span>,

<abbr class="country-name" title="United Kingdom">UK</abbr>

</span>

(<span class="geo">

<span class="latitude">50.818967</span>,

<span class="longitude">-0.151934</span>

</span>)

</p>

</div>Where Next for Geo HTML?

As you’ve seen, there are a number of different types of content that can be enhanced with the geo microformat. However, at present, the microformat can only describe solitary, one-dimensional points. Formats such as GeoRSS, KML and GML, on the other hand, can also handle altitude, lines, areas and volumes. This is useful for describing streets, paths, boundaries, city and country territories, 3D buildings and natural features.

It remains to be seen whether such sophistication will make it into an HTML standard, or whether we will use HTML to embed external geo objects. These objects could be coded in a more specialised language, just as we currently embed JavaScript files and CSS stylesheets. Such discussions are well under way.

The Future of Geo

In this article, we’ve explored some of the newest developments in geocoded content. Whilst mapping itself is an ancient pursuit, we are beginning to see the promise of a new kind of cartography. When we reach a critical mass of geo content and a wider distribution of geo applications and hardware, we can expect to see a very different Web than the one we know today.

Figure 12: Google Earth, showing a 3D Empire State Building with Wikipedia content.

We are starting to see geo-awareness being built into everyday devices – including phones, computers and cameras. In the same way that clocks are now used to time-stamp the messages we send and the pictures we take, we may in future take it for granted that they geo-stamp our data too.

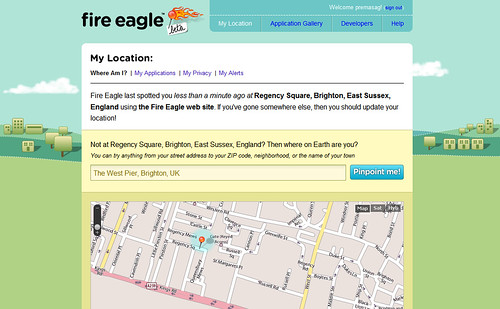

It may also become common practice to update a web service, such as Fire Eagle (Figure 13), with one’s current location – a practice that we might call “geoscrobbling”:

Figure 13: Yahoo Fire Eagle.

The record of a person’s position over time could be used to place anything that they publish onto a Map, or could be streamed to their friends, or to web services that have permission to access it. And yes, you can also expect a flurry of discussions on geo privacy and security.

Perhaps future camcorders will track their position as they record – quite literally, filming on location. Could something like Yahoo Live + Fire Eagle be the future of mobile video?

Summary

Geo is the most physical of all web technologies. It offers us a chance to reconnect with our local communities and to discover those around us. And as the world grows closer, we will start to see ourselves on each other’s maps. So, watch this space… (and that space… and that one)…

3 Trackbacks

[…] – Links4meRogers BlogFamilie, Freunde, Sachen…2008-04-24Links4me Von roger @ 00:15 [ Diverses ] Location Based Publishing and Services Geocoded content is transforming our Web. By adding geographical coordinates (latitude and […]

[…] public links >> hcalendar Location-Based Publishing and Services First saved by lkkjooio | 0 days […]

[…] (Island Press, 9781597265881) will be on the Diane Rehm Show on Wednesday, October 21st. …Location-Based Publishing and Services : DharmaflyI have recently had a technical article about Location-Based Publishing and Services published at […]